As a field officer tasked with foreign intelligence collection (or more active operational duties), the intelligence field is certainly a darkly frustrating trade. What can one man (or woman) do in the face of powerful and vast governmental power? Yet, in certain moments, particularly those characterised by political instability, the individual does have the power (though often unwittingly, even accidentally) to be the catalyst for dramatic change.

Coincidentally, I was recently pointed to Günter Schabowski’s obituary in The Economist by the inestimable Flight Risk fan Shylock Holmes (along with the proviso that the only thing worth reading in The Economist anymore is the obituaries). One sees this “fateful but unknowing lynchpin” effect in “One Little Word” (the Schabowski obituary) as an evening audience given by Schabowski (then First Secretary of East Berlin and member of the Politburo) and colleagues on November 9, 1989 is described and, in particular, the response to a question about freedom of travel rules (or lack thereof) in East Germany:

The Politburo had discussed travel the day before; he was out of the room. But Egon Krenz, the new party leader, had thrust a note into his hand before the press conference—just like a shopping list, clucked Irina—on which were scrawled four points, the fourth blazoned with a big red arrow. He had put it in his briefcase after a skim-read of it, and now had to work it out publicly with everyone listening. Uncharacteristically, the swaggerer began to stammer. “We have decided today…um…to implement a regulation that allows every citizen of the German Democratic Republic…um…to…um…leave East Germany by any of the border crossings.”

The question came: “When?” And he answered, scratching his head and shuffling papers, “Sofort”. Immediately.

He was wrong on the facts: there was meant to be a delay until 4am the next day, so that the border guards could be alerted. But in any case he did not mean “immediately” in the Western sense. This was East Germany. Everything worked in a slow, grinding, disciplined way. On the cheerless public stairways of his apartment building, overlooking both the Wall and the ruins of Hitler’s bunker, a notice ordered everyone to stick to the cleaning rota “or organise your own replacement”. People wishing to leave would obey the rules, forming a queue at the appropriate state agency with their blue identity cards to get their new visas stamped. This was what he anticipated; not what actually happened, which was a stampede of reporters out of the room and East Berliners, with hammers, to the Wall. And that was that, he instantly knew, for East Germany.

Unsurprisingly, accusations that Schabowski was a foreign agent sprung up immediately, and were harboured not least, and to a man, by the rest of the Politburo. Such a momentous change hinged on such a small moment could only point to the most heinous example of sabotage, of course. He was expelled from The Party with immediate effect, and suspicions haunted him for years.

In the fullness of time, the general consensus became that Schabowski simply misspoke, but, then again, that would be exactly what he would want you to think, wouldn’t it?

In the fullness of time, the general consensus became that Schabowski simply misspoke, but, then again, that would be exactly what he would want you to think, wouldn’t it?

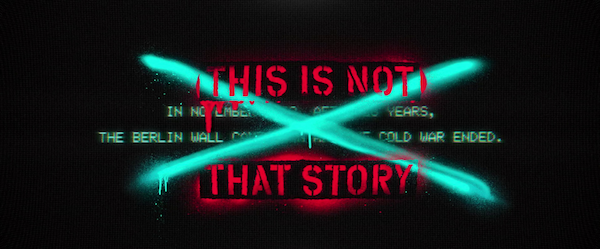

The Politburo’s concern was in some sense understandable. Drama was always a key element of Eastern propaganda (The Soviets effectively invented “agitprop”, a term drawn from the literal “Department for Agitation and Propaganda”), and counterintelligence assets in the Warsaw Pact countries were always anxious to spot the intricate and subversive machinations of “The West” lurking around every corner. It is no accident that the classic cold war spy story takes more than a little dramatic license with her characters, granting them no small measure of prescience, of agency, and certainly an immediate awareness of the gravity of the events around them, a gravity closely bound to the pivotal importance of their own role. Atomic Blonde (2017), (which, for reasons I hope will soon become apparent, I have been itching to parse for some time) as it hastens to tell you, is not that story.

Those expecting Atomic Blonde to be nothing but a stunt-fest might be forgiven their assumptions given the action-cred origin story of director David Leitch (“John Wick”, “Deadpool 2”), but a pleasant surprise awaits the viewer who arrives to the film with those biases in place. The source material (the graphic novel “The Coldest City“) takes quite some advantage of its long-form to weave a dauntingly complex plot that would at first blush seem to discourage any attempt at film adaptation, but it is a challenge Leitch and screenwriter Kurt Johnstad (“300”, “Act of Valor”) take on, and then master.

For all its plot complexity, Atomic Blonde emerges as a wonderfully accessible film, one in which its main characters struggle with their own weaknesses, flaws, and failures, even as what might be argued as the ultimate climax of the Cold War battle between East and West is laid bare. The promise of the West, favourable as it may be, is not utopia any more than the flagging East, and the primary agents in the battle seem to have long before lost all illusions about the nobility of their cause, and yet, from this cynical backdrop emerges a surprisingly uplifting argument for individuality (particularly of the feminine variety).

Early on there is something different about Atomic Blonde, and as you slip deeper into the film the exercise in contrasts that underpins it becomes apparent. Director of Photography Jonathan Sela’s (“John Wick”, “Deadpool 2”, and, wonderfully, Miley Cyrus’s “Wrecking Ball” video) use of colour evokes shades of Nicolas Winding Refn (it is impossible not to think of “Neon Demon”, and “Only God Forgives”). It is impossible not to think that the decision to set the simply electric Charlize Theron (“Mad Max: Fury Road”, “The Devil’s Advocate”) against the hue of her surroundings (or drown her in it) is deliberate.

Between this, adroit use of Berlin as a set (those familiar with the city will be transported back there easily), and a masterful bit of editing by Elísabet Ronaldsdóttir (“Deadpool 2”) the immersive effect is complete even before the signature ’80s soundtrack is fired up (using the German version of “Major Tom” as a lead-in and background for Theon’s first major fight scene is but one example of the genius expressed in the attention to detail here).

Many female leads in action films present issues for directors, and with those issues a nearly inevitable trade off: either dumb-down the action, or sacrifice realism with CGI. Here Theron and Leitch are at their symbiotic best. The Director’s commentary is essential listening for the aficionado (though it should be saved for the third or fourth viewing of Atomic Blonde), not least because it lays bare the degree to which Theron was an active part in the choreography and execution of her fight scenes. Proper firearms handling is a Leitch trademark, and all across the film he (and, one assumes the 87Eleven team) are at the height of their craft.

It lingers just beyond the perception with early viewings but, especially for those clued-in by the Director’s commentary, the use of reflection, confusion, and pure craft in photography surrounds Theron’s Lorraine Broughton with the byzantine machinations of conflicting powers (not to mention agents with their own private, ulterior motives). Throughout Lorraine transforms herself to blend in to (and, in some cases, stand out from) her environment, and in this she almost perfectly mimics the Cold War warriors she is an amalgam for.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Atomic Blonde 2 has been announced already. Here’s hoping Leitch returns for a reprise.